Caroline Ashley was born in Ashford, Connecticut on July 14, 1824 to Samuel Ashley and Lydia Franklin (Olney) Ashley. Though her family lived in Connecticut before moving to Providence, her mother Lydia descended from the original Olney and Whipple arrivals in Providence in the 1630s. Her father, Samuel, descended from Robert Ashley, one of the original inhabitants of Springfield, Massachusetts. He worked as an attorney at law in Providence until his death in 1855. Caroline undoubtedly learned much of her own moral drive from her father. In his Reminiscences of the Rhode Island Bar, Abraham Payne wrote that Samuel Ashley was unconcerned with "fat contentions and flowing fees” and “gained none of the prizes for which men contend--wealth nor power nor fame,” but rather “he fought a good fight.” Ashley’s law was the kind “whose seat is the bosom of God, and whose voice is the harmony of the world,” and he was most at ease “in the higher regions of thought.” He admired men of intellect and action, like the Hungarian Louis Kossuth, and carefully studied the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg. His moral character was apparently unparalleled and Payne concluded, “His hands were clean, his purposes were pure, his courage never failed; he had the respect of all who knew him, and above all he had his own self-respect." Both Samuel and Lydia are buried at the North Burial Ground—their graves marked by the same stone as Caroline’s. Caroline apparently always lived with some combination of her parents, her siblings and their spouses, throughout her life.

We know little of Caroline Ashley beyond her occupation as a teacher and her participation in the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. She is mentioned in a number of documents related to this organization and Elizabeth Buffum Chace, the great suffragist and abolitionist, thanked her by name in an 1889 address about the roots of women’s suffrage in Rhode Island that recalled a handful of the most significant contributors to the abolitionist cause in antebellum Rhode Island. Through their work in abolitionism, women learned much about themselves, their fellow women, and the social and political realities of American life. As historian Julie Jeffrey concluded, “Above all, abolitionism had tested women’s understanding of what it meant to be female.”

We know little of Caroline Ashley beyond her occupation as a teacher and her participation in the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. She is mentioned in a number of documents related to this organization and Elizabeth Buffum Chace, the great suffragist and abolitionist, thanked her by name in an 1889 address about the roots of women’s suffrage in Rhode Island that recalled a handful of the most significant contributors to the abolitionist cause in antebellum Rhode Island. Through their work in abolitionism, women learned much about themselves, their fellow women, and the social and political realities of American life. As historian Julie Jeffrey concluded, “Above all, abolitionism had tested women’s understanding of what it meant to be female.”

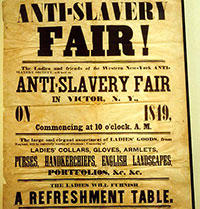

The Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1835 (see Sally Goddard on this tour), shortly after the male society, a fact that reminds us of Rhode Island women’s essential role in abolitionism even at a time when their own rights were so limited. The female society mainly focused on fundraising through the sale of homemade products at fairs, though they also engaged prominent orators and published antislavery pamphlets such as the 1845 volume Liberty Chimes.

Abolitionists across the north relied on the fairs to raise the funds necessary to keep their organizations running. The larger cities of Boston and Philadelphia hosted huge affairs that drew from surrounding states. In Providence, the market was combined with a formal tea and supper for subscribers. People of all ages and from all over the state donated their handiwork, money, and time to support the cause. The fairs brought together all kinds of people who were energized and encouraged in their abolitionist work by the communal show of support.

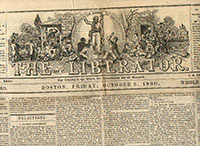

Caroline Ashley’s name appears on the announcement for the Providence “Anti-Slavery Fair” that was published several times over the summer of 1844 in William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator. The fair was held in September of that year. The advertisement stated that the ladies of the Providence society felt that “more energetic and decisive action” must be taken. It exhorted Rhode Islanders to participate: “Your purses, your farms, your workshops, your factories, and your stores, we expect will be laid under liberal contribution. Things to eat and things to drink, things to be seen and things to be worn, things useful and things fanciful, let them come, in overwhelming abundance. Nothing can be too numerous, too great or too small. We ask each of you to do something. Form at once sewing circles and knitting societies, organize and send forth efficient soliciting committees. Let no person remain idle or unsolicited…” The language was both incendiary and calculating, reminding Rhode Islanders of their special heritage of liberty and warning that the “foes of freedom are mustering strong, even now, and the battle waxes hot.”

Caroline Ashley’s name appears on the announcement for the Providence “Anti-Slavery Fair” that was published several times over the summer of 1844 in William Lloyd Garrison’s Liberator. The fair was held in September of that year. The advertisement stated that the ladies of the Providence society felt that “more energetic and decisive action” must be taken. It exhorted Rhode Islanders to participate: “Your purses, your farms, your workshops, your factories, and your stores, we expect will be laid under liberal contribution. Things to eat and things to drink, things to be seen and things to be worn, things useful and things fanciful, let them come, in overwhelming abundance. Nothing can be too numerous, too great or too small. We ask each of you to do something. Form at once sewing circles and knitting societies, organize and send forth efficient soliciting committees. Let no person remain idle or unsolicited…” The language was both incendiary and calculating, reminding Rhode Islanders of their special heritage of liberty and warning that the “foes of freedom are mustering strong, even now, and the battle waxes hot.”

Despite this effort, abolitionist activity declined in the 1840s. Some women became more involved with the issue of women’s suffrage and less involved in abolitionism. The decline may have followed the violence of the Dorr Rebellion in Rhode Island, as well as mob violence related to the slavery issue nationwide. Caroline Ashley wrote to Thomas Dorr on September 5, 1842, in the midst of the crisis, on behalf of the “young ladies of Providence who sympathize with you in your efforts to help the people of Rhode Island.” Clearly she saw a connection between Dorr’s fight and abolitionism. She sent him a pocket bible as a sign of the “deep interest we feel in the cause in which you are engaged” and she lamented that “one of its abilist [sic] advocates remains of necessity in exile from his home state.”

At some point before 1862, Caroline Ashley became a teacher and also the assistant to the principal at the Meeting Street Grammar School in Providence. It is not known when or if she retired. She continued to live with her siblings in Providence until her relatively early death on November 16, 1884, just months after her mother’s death that June, and was interred alongside her parents in the North Burial Ground.

Erik Christiansen, PhD

Further Reading:

Bacon, Jacqueline. The Humblest May Stand Forth : Rhetoric, Empowerment, and Abolition. University of South Carolina Press, 2002

Jeffrey, Julie Roy. The Great Silent Army of Abolitionism: Ordinary Women in the Antislavery Movement. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 1998.

Yellin, Jean Fagan and John C. Van Horne, Eds. The Abolitionist Sisterhood: Women's Political Culture in Antebellum America. Cornell University Press, 1994.

Roedigger, David and Martin H. Blatt, Eds. The Meaning of Slavery in the North. Garland Reference Library of Social Science, 1998.

Van Broekhoven, Deborah Bingham. The Devotion of These Women: Rhode Island in the Antislavery Network. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2002.

Caroline Ashley was born in Ashford, Connecticut on July 14, 1824 to Samuel Ashley and Lydia Franklin (Olney) Ashley. Her mother Lydia descended from the original Olney and Whipple arrivals in Providence, beginning in the 1630s. Her father was an attorney in Providence, known for his unsurpassed morality. Caroline Ashley worked as a teacher and was deeply involved in the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. Elizabeth Buffum Chace, the great suffragist and abolitionist, thanked her in a speech about the roots of women’s suffrage that recalled the most significant contributors to the abolitionist cause in antebellum Rhode Island.

Caroline Ashley was born in Ashford, Connecticut on July 14, 1824 to Samuel Ashley and Lydia Franklin (Olney) Ashley. Her mother Lydia descended from the original Olney and Whipple arrivals in Providence, beginning in the 1630s. Her father was an attorney in Providence, known for his unsurpassed morality. Caroline Ashley worked as a teacher and was deeply involved in the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. Elizabeth Buffum Chace, the great suffragist and abolitionist, thanked her in a speech about the roots of women’s suffrage that recalled the most significant contributors to the abolitionist cause in antebellum Rhode Island. We know little of Caroline Ashley beyond her occupation as a teacher and her participation in the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. She is mentioned in a number of documents related to this organization and

We know little of Caroline Ashley beyond her occupation as a teacher and her participation in the Providence Ladies Anti-Slavery Society. She is mentioned in a number of documents related to this organization and  Caroline Ashley’s name appears on the

Caroline Ashley’s name appears on the