Student Essay

View or download essay

Jenney Martinelli

450 Warhol

WARHOL AND MONEY 1960s-1980s

Andy Warhol returned to money in the early 1980s when he began his series of screen prints titled Dollar Sign. The subject was familiar as he explored this theme in the early ‘60s with naturalistic drawings of paper currency. Two decades later, Warhol took a new approach with visually arresting vibrant variations of neon colors. Rhode Island College has a print from the later series that is purples, aqua, and bright orange. Currency was the forefront of this series, with the dollar sign taking up nearing the entire composition. With the later series, Warhol reinforces the importance of money, he questions the psychological impact of consumer culture and the correlation between wealth and success, and he addresses the use of business art to excel in the art market.

While research on Warhol’s Dollar Sign is limited, literature about the art market, financial behavior, and the role of money in Americans’ lives provides useful context for seeing the cultural reverberations of the RIC print. Generally, scholars agree that Warhol was fascinated with money and with things that generated money. In Andy Warhol Enterprise$, Sarah Urist and Allison Unruh identify money not only as a direct subject, but also an indirect theme in Warhol’s use of iconic personalities like Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley. Some assert that Warhol’s use of financial iconography is obvious but that undermines the nuance of his vision. As Unruh claims, his depictions of money are multifaceted and complex. Urist notes that Warhol’s financial success was very real-- he knew the inner workings of the art market-- and refers to Warhol’s money paintings as relative to the “production and reception” of art. In Art and Money, Peter Stupples says, Warhol shocked the art world with his open discourse about money. Perhaps Dollar Sign’s poor reception was due to its snub from fine art world propriety though it was stylistically in line with much of the work Warhol produced in the previous decades.

The Dollar Sign series consists of approximately 60 silkscreen prints on paper made between 1981 and 1982. Rhode Island College’s 16 x 20-inch print displays a large central dollar sign printed in three layers. Screen printing is generally created in registers, or layers, from the base layer to the front most layer. Here, the background is filled with a mid-tone purple. Over that is a lighter purple shade in the shape of the dollar sign filled solid as is the background color. The second layer is an aqua blue color with similar value to the light purple. Besides hue, what differentiates this layer from the previous one is that the solid fill is textured as if colored by crayon with a jagged “hand drawing” outlined line and fill. This aqua layer stands out because it is printed slightly askew from the previous lavender layer. The last layer of Dollar Sign is inked vibrant orange except for a blended ombre of red on the bottom left serif. It is filled with a similar texture of “hand colored” marking as the aqua, but with a thicker, heavier mark so that the solids are opaque and the middle section is open. The symbol is itself italicized to reveal the layers beneath. The compilation of colors and textures makes this artwork exciting and eye catching.

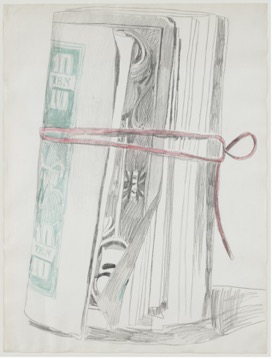

From early childhood, Warhol was excited about celebrities, their fame, and their fortune. Growing up in a working class immigrant family, money seemed to be far from reach. As an adult, Warhol talked a lot about money, as seen in an entire chapter titled “Economics” in his Philosophy of Andy Warhol. Throughout his successful career Warhol made many depictions of money including dollar signs and dollar bills. Among his most famous works are 200 One Dollar Bills (fig. 2), and Roll of Bills (fig. 3), both from 1962 and the Dollar Sign from 1981 to 1982.

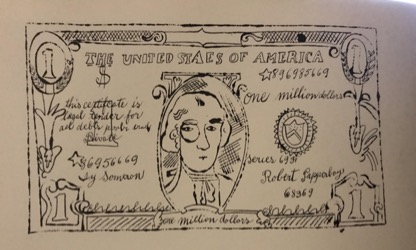

Warhol’s career began as a commercial artist in 1950s New York City with great success. Line drawings of dollar bills at this time used a blotted line technique as seen in his One Million Dollar Bill (fig. 4) from the 1950s. Interestingly, Warhol never dropped the title of commercial artist, but by the 1960s he dropped his blotted line technique for more refined pencil drawings and worked to gain access to the “fine art” market. He continued to explore traditionally non-fine art images in commercial art mediums.

His practice of commercial art techniques, such as silk screening, were shamed by his contemporaries, but Warhol had a fascination with “Business Art” an idea that the act of making money is art, and that staying in business is the best art practice. By the 1970s, he was a well known artist and made upwards of $20,000 each for commissioned society portraits while continuing to depict prominent figures including Chinese Communist leader Mao Zedong. He also experimented with several conceptual series such as Oxidation, Shadows, Retrospectives and Reversals.

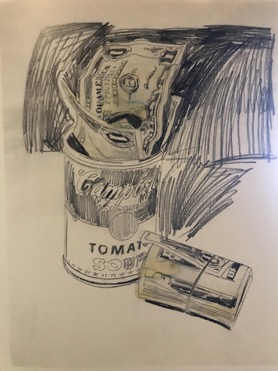

Prior to the Dollar Sign, images of money had never permeated the fine art market. Warhol combines currency with a mundane consumer product in his drawing Campbell’s Soup Can and Dollar Bills from 1962 (fig. 5), but later work was more discreet. For example, 200 One Dollar Bills depicts money with slight variations in the application of ink. Some are over-printed so that some ink appears dark and bold, other ink is light leaving only faint prints of the image. The 1981 Dollar Sign series is bold and brilliant in style and subject.

“I like money on the wall. Say you were going to buy a $200,000 painting. I think you should take that money, tie it up, and hang it on the wall. Then when someone visited you the first thing they would see is the money on the wall.”

Warhol’s work questions what it means to own art. He equates artwork with money and toys with the idea that money is prestige. In his Philosophy, Warhol says how exciting it is to have cash, and suggests that if readers don’t have it, they pretend they do. By 1981, when RIC’s print from the Dollar Sign series was made, Warhol was so popular, owning a work by him was sought after and expensive, regardless of the number of prints in the series. Like the printing of currency, Warhol mass produced images at different points of monetary value for the art market.

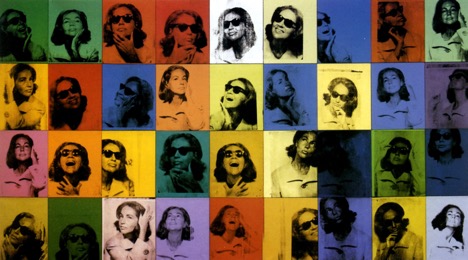

To commission a well-known artist for a portrait is a sign of wealth and prestige and Warhol is well-known for his commissioned society portraits, for which many of the Polaroid portraits in this exhibition were made. Perhaps most spectacular is the early painted portraits of Ethel Scull (fig. 6). In 1963 Warhol photographed Scull as part of the process for fulfilling her commission. The final artwork references the nearly 300 Polaroids from her photoshoot in a whopping 6 1/2 by 12-foot tableau of 36 individual representations of her. While this portrait is less overtly spectacular than one of, say Queen Elizabeth, its size and brilliance of color, paired with the repetitive image of Scull’s face, suggest the sitter’s wealth and prominent social position as much as her playful personality.

Similarly, the repetition of the dollar sign in its series mirrors the repetition of Scull’s face. Wealth and success are linked in society portraits and depictions of money. The Dollar Sign series uses vibrant colors in variations reminiscent of the different compositions in Scull’s portrait. Warhol flattens out content, even layered three times, for more prominent iconography so that the importance of money is upfront in its larger than life symbol.

While portraiture was a consistent genre in Warhol’s career from the 1960s to his death in the 1980s, money was a subject Warhol explored in the 1960s, then ignored, and only returned to two decades later in the 1980s at a time of controversial economic policy reforms. Cash was something that Warhol liked to have and liked to spend. In “Can’t Buy Me Love,” Mario Mikulincer examines what the implications of making or having money. He expands on the theory that money can act as a barrier to psychological pain for people who are not getting love and support elsewhere. A team of psychologists including Thomas Tang conducted experimental research to determine the effect of money on the psyche. One conclusion asserts that people with high work satisfaction have a positive relationship with money.

Warhol wrote about his relationship with money in his diaries, but there has been little evaluation of the health of that relationship, even as the theme of money is threaded throughout his career. He tracked every detail of his expenses to keep diligent records. His depictions of paper money in a still life hints at this fiscal practice. But why the shift to the symbol of money rather than currency itself? Perhaps the financial culture inspired him to distill money further.

In 1981, Ronald Raegan became president and a major change was his reforms called Reaganomics, a “trickle down” economic system. Reagan’s government granted tax cuts for the rich expecting that they would invest in the economy, which would expand causing financial benefits to trickle down to the middle and working classes. However, it was a failure. The result was tax increases for the middle and working class, increased inflation, and increased government spending including military spending while the rich got richer.

Whether or not Warhol agreed with Reagan’s policies is not clear. Although Warhol was wealthy by this point in his life, it’s possible that this shift made him uncomfortable. One could argue that Warhol uses the symbol of money in this case to bring attention to the changing economy. The layering, obscuring, and manipulations of the RIC image with the mid-tone purple and lavender hidden by fake “hand-drawn” dollar signs seem to imply duplicity in a system that ignores layers or socio-economic classes hidden by others.

Yet, Warhol also seems to be acknowledging his monetary success. The first images of money in the 1960s come at a time when he initially earned success in the commercial world. After his near-death experience in 1968 and the lull of personal work in the 1970s, the 1980s gave Warhol space to reflect on his achievements. The Dollar Sign series coincides with “business art” in which Warhol asserts that money is positive, and that working for and earning monetary success is good. He says that Business Art is the step that comes after art. After denouncing painting so many times, perhaps he expresses he was in his business art phase which seems to encompass all the things artists need to do to keep themselves active and relevant.

Ultimately, Warhol was successful on much of his own terms. He and his Factory produced work every day, and he prospered financially as a result. He was self-aware and used business art to his advantage. The Dollar Sign series comments on consumer culture, and what it means to have money as well as to larger societal issues through the eyes of Andy Warhol.

Figure 1: Andy Warhol, Dollar Sign, 1981

Figure 2: Andy Warhol, 200 One Dollar Bills, 1962

Figure 3: Andy Warhol, Roll of Bills, 1962

Figure 4: Andy Warhol, One Million Dollar Bill, 1950s

Figure 5: Andy Warhol, Campbell’s Soup Can and Dollar Bills, 1962

Figure 6: Andy Warhol, Ethel Scull 36 Times, 1963